Topics: DevOps, Networking

(Disclaimer: No AIs were used in the writing of this article. My intelligence has been frequently questioned, but has thus far never been accused of being less than natural.)

At this point, it's fair to say most tech-oriented cyberspace denizens have at least a passing familiarity with the basic concepts of HTTPS. Back in Ye Olden Times, that meant buying a cert from a company1 once a year and installing it on your web server. These days, we have free public certificate authorities whose APIs are baked right into the server software or are easily bolted on. So there is not generally as much need to understand the vagaries of the certs themselves as there was before.

But what happens when the magical cert-fetching mechanisms fail and you don't know why? Or you need something that a public CA cannot provide for whatever reason? Well, when that happens, please do feel free to drop me an email to ask about my rates. :) Or, if you must, fall back to Plan B and read the remainder of this article to learn about the most important, practical bits of how HTTPS and SSL/TLS work.

This is loosely based on a talk I gave at work, where a few developers on a neighboring team had questions about how to configure and troubleshoot certificates in their server software. The goal here is to show how certs work at the most basic conceptual level, without straying too far into RFCs and X.509 and what have you.

Background

First off, you may be asking yourself, what's the difference between SSL and TLS? The answer is: None. None at all. They are just different versions of the same thing. What happened is that the protocol was initially named SSL (Secure Socket Layer) and as it went through revisions, someone decided to call it TLS (Transport Layer Security) instead. That was decades ago but due to inertia and the inability of anything on the Internet to ever truly die2, people still call the technology both "SSL" and "TLS" and use the two acronyms completely interchangeably. So that's fun.

The rest of this article, I'm going use "TLS" because that feels like the most correct thing to do.

HTTPS is ostensibly just HTTP (hypertext transfer protocol) with TLS layered on top of it. Layers are good because that means they can be interchangeable and individually upgradable. TLS can be layered on top of other protocols such as FTP, IMAP, SMTP, IRC, etc. But HTTPS is far and away the most popular use case.3

TLS gives us two fundamental properties of a secure information exchange: encryption and trust. Encryption is the process of transforming information of any kind into an opaque blob of data that only the sender and receiver can decode back into its plaintext form. Someone else in the path of the encrypted data can see that it's there, but cannot read the information while it is encrypted because it just looks like random nonsense. The trust component ensures that you are talking to someone who is who they say they are. The SSL/TLS designers decided that encryption was totally and utterly useless without trust, so both of these were combined into the one thing, thus ensuring Internet flamewars for generations to come.

Any software that hosts a TLS service (e.g. HTTPS) needs at least two things for a valid configuration:

- A private key

- One or more certificates

Private keys are considered secrets. (Like your passwords, but totally random and much longer.) "Keep it secret. Keep it safe."

TLS certificates and keys are X.509 structured binary data, but we most often see them encoded in PEM format for easy transport between systems, software, and people. (And clipboards.)

A private key looks like this:

-----BEGIN PRIVATE KEY-----

MIIEvQIBADANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQEFAASCBKcwggSjAgEAAoIBAQDdwRCbSS3MBX0Z

V063D0GRGqTMJp2Tla+3ICuVXffJR2QPH41r08vHOPz3bikFL3lu3d6uZMlkOKJU

... many lines of data ...

LwhR0trxBvI9mPXw9NbiLzdabL7UJ+bW36o5FBsevDoJ8i6tHmrMZ55H/W6G0h5d

zq3Af0aj6XNl7ky2fbgw78Q=

-----END PRIVATE KEY-----

A certificate looks like this:

-----BEGIN CERTIFICATE-----

MIIG8zCCBdugAwIBAgIRALuuT/h77hmJFbbXENERxHIwDQYJKoZIhvcNAQELBQAw

gZUxCzAJBgNVBAYTAkdCMRswGQYDVQQIExJHcmVhdGVyIE1hbmNoZXN0ZXIxEDAO

... many lines of data ...

b1nH99Re7ArYen3dKsgk/chlIHowdIKk7mTL3DTIck5PUaWmn9P8wg851EONxPnP

YtTVdTaXNg==

-----END CERTIFICATE-----

I highly encourage you to play around with tools that let you generate your own certificates. Try it with raw OpenSSL, or GnuTLS, or download a sketchy shell script from a GitHub gist, whatever. This article doesn't have any instructions for this because there are already eleventy-billion blogs on the web that do.

Chain of Trust, Part 1: Vocabulary

A Certificate Authority (CA) is an entity which signs certificates. An "entity" here is usually an organization of some kind. But it could be a small team, a department within your company, or a single individual. A CA is intended to be someone you trust to secure network communications on your behalf.4

When a CA signs another certificate, they are vouching for the trustworthiness of the person or organization in control of the private key for that certificate. It does this using some fancy mathematics that we call cryptography. If your software trusts a CA, it uses the same fancy mathematics to verify that the certificates it receives was signed by a CA that you trust.

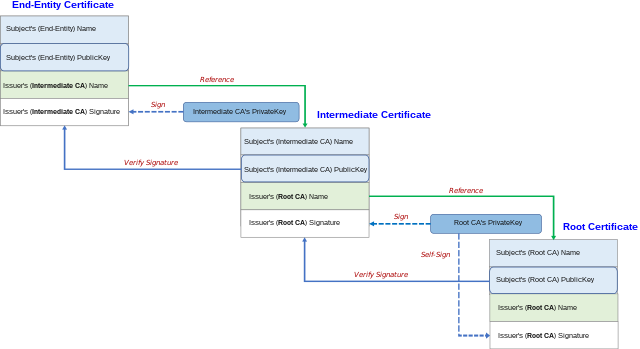

There are three kinds of certificates which form a chain of trust:

- Root certificates

- Intermediate certificates

- Leaf certificates5

A root certificate (a.k.a. root CA cert) is generated by a CA and is self-signed, meaning the Issuer and Subject fields are identical. It is also marked as a CA cert in the certificate extensions. Although technically possible, root certificates are not typically used for directly signing leaf certificates because the time and effort cost of replacing them is usually high. They are generally created with a validity of many years, perhaps a decade or so. Their private key is (or should be) held in a secure location and is only brought out on special occasions to sign new intermediate certs.

An intermediate certificate (a.k.a. subordinate CA cert) is also generated by a CA, but has a shorter validity than a root, and is used to sign either other intermediate certs, or leaf certs. These can be signed either by a root CA cert or another intermediate cert. These are also marked as CA certs in the cert's extension fields. Intermediate certs are never self-signed.

A leaf certificate (a.k.a. end-entity cert, or server cert, or service cert) contains the server's public key and (usually) proof of ownership/trust by virtue of being signed by a trusted CA. A leaf certificate can also be self-signed, in which case the TLS connection still works, but users will get warned by their client that the certificate is not trusted. (Unless the cert is added it to their browser as a trusted cert.) Leaf certs contain special fields to show what the cert is authenticating, which in the case of HTTPS is the DNS name of the site.

Anatomy of a Certificate

There are oodles of tools that can inspect an certificate, but OpenSSL is ubiquitous:

openssl x509 -in <cert_file> -text

This is what you get:

A cert has many bits of information, but these are the most important ones:

- Issuer: Who issued (signed) the certificate.

- Subject: What the certificate is for. If the Subject and Issuer are exactly the same, that is a self-signed cert and possibly a root cert.

- Side-note: The subject contains a CN (CommonName) attribute. Once upon a time, this was used to specify the domain that the certificate was created for. In modern times, the CN attribute is largely ignored by TLS clients, which only look at the Subject Alternative Name (SAN) if it exists. See below. (But note that some "legacy" software may still try to validate the CN.)

- Validity: When the certificate is valid.

- X509 Extensions:

- Subject Alternative Name (a.k.a. SAN): In a leaf cert, this contains one or more DNS names and is what links the site security to the certificate. This can be an FQDN or a wildcard (e.g.

*.example.com). It's important to know that wildcards do not include subdomains, so*.example.comwill not work forfoo.bar.example.com. - Key Usage: Root and intermediate certs will say "Certificate Sign", leaf certs will say, "Digital Signature"

- Basic constraints: Root and intermediate certs will say "CA: True"

- Extended Key Usage: Leaf certs will say "TLS Web Server Authentication"

- Subject Alternative Name (a.k.a. SAN): In a leaf cert, this contains one or more DNS names and is what links the site security to the certificate. This can be an FQDN or a wildcard (e.g.

Every certificate has a matching private key that should be kept secret. Ideally, it should be generated on the device/host it is for and never leave that host for any reason. But the reality is that sometimes we have to copy keys around just to get the job done. Avoid putting the key in email, or on some public or semi-public system. If you must copy it somewhere, at least take some time to think about the most secure way of getting it there.

Chain of Trust, Part 2: Machinery

Web browsers, operating systems, and other client software ship with a set of root certificates from organizations that they consider trustworthy. There is generally a vetting/audit process that browsers and OSes make CA's jump through in order to get their root CA cert shipped in their software. If the root CA cert is installed on your system, then it is trusted. This is essentially the entire basis of security on the web as we know it today. (For better or worse, depending on your experience and opinions.)

Users and companies can optionally decide to trust their own root CA certificates by placing them in the root certificate store of the OS and browsers of the computers they manage. Et voila, you now have an internal certificate authority. This is a very practical choice when using public CAs is onerous for whatever reason, or when you require a higher degree of trust/security than the public CA vendors can promise, at the non-trivial cost of extra administration tasks and workflows.

TLS clients decide whether a certificate is trusted by walking backward from the leaf cert to the root. Using a web browser to illustrate an absurdly oversimplified example:

- When the browser connects to an HTTPS website, the server sends one or more certificates:

- The leaf cert

- Zero or more intermediate certs (one to two is most common)

- The browser looks at the leaf cert and compares the domain in the URL bar with the SANs in the leaf cert. If there is a match, the browser knows that the certificate is at least the correct one for the website, and proceeds to verify the chain of trust.

- The browser looks at the leaf cert's subject and signature, and tries to find an already-trusted root cert matching those. If it does not, it looks at any intermediate certs that were sent by the server.

- The browser looks at the intermediate cert's subject and signature, and tries to find an already-trusted root cert matching those. If it does not, it looks for any further intermediate certs that were sent by the server. This step repeats until a root cert is found.

- If the browser finds a matching root cert in its certificate store, then all of the certs downstream are considered trusted, and the HTTPS connection is allowed to continue.

If any of the above steps fail, the browser declares the chain of trust to be broken, and will throw an SSL/TLS error. Quite often accompanied by a cute cartoon that some UI designer thought might somehow lessen your frustration with their product.

Common Configuration Patterns

In the days of yore, server software required these to be split up into multiple files and specified as separate configuration items. (Many still do, especially those that can be configured only through a web interface.) For example, Apache used this:

# leaf cert, intermediate cert (or bundle), and key respectively

SSLCertificateFile /etc/ssl/certs/foo.example.crt

SSLCACertificateFile /etc/ssl/certs/EXAMPLE-CA.bundle

SSLCertificateKeyFile /etc/ssl/private/foo.example.net.key

Nowadays, you can get away with:

# everything in one file

SSLCertificateFile /etc/ssl/private/foo.example.net.crt

Some software only has fields for the certificate plus intermediate certs, and the private key.

However, most server software is moving toward the practice of bundling all certificate materials into one file. When this is done, you generally must specify the certs/key in a particular order in the file, that order being:

- The leaf certificate

- Any intermediate certs (each cert below the one it signed)

- The private key

Note that the root CA is nowhere in here. Servers don't need to send root certs to clients, although it usually will not hurt anything if they do.

How to know if your server software supports concatenating the certs and key into one file?

- RTFM

- Just try it

Verifying Certificate Configuration

It's important to know that web browsers can and do cache intermediate certificates that they have seen before. So if you have inadvertently left out an intermediate certificate on a server configuration, the web browser will say, "oh, I've seen that one before, I'll just grab it from my cache" and proceed to verify the chain of trust using the intermediate cert(s) that it dug out from between the couch cushions rather than noticing that the server didn't even send one. And it will show the site as trusted and everything will look normal, until another user with a different browser visits the site and gets an SSL error and kicks over every trash can on his way to your desk to berate you for "breaking the network."

This is why you should always verify that the certificates are correct with another tool. Naturally, OpenSSL can do this:

openssl s_client -connect <hostname>:<port> -servername <hostname>

The output has essentially has these sections:

- The chain of trust. This shows the subject of each certificate in the trust chain, starting with the root and ending with the leaf, with any intermediates in between.

- The "Certificate chain" as sent by the server, starting with the leaf cert, followed by intermediate certs. It shows the subject, issuer, and validity period of each cert. This is generally the one you want to pay the most attention to.

- The leaf cert in PEM format.

- TLS handshake details. The most important part here is near the end a line that says, "Verify return code" which will be

0if the whole chain is trusted.

Non-Public Root CA Certs

All of this depends on your OS having the correct root certs installed, and OpenSSL knowing where to find them. For most publicly-trusted CAs, this generally Just Works but if you have a custom root CA in your company or team, you probably have to manually install the root CA cert in your browser and/or on your operating system. Figuring out how to do that for your OS or browser is left as an exercise to the reader since it varies greatly by product.

But for those running a Debian or Ubuntu Linux distribution, I'll make it easy because they make it easy:

- Copy the root CA cert to

/usr/local/share/ca-certificates - Run

update-ca-certificatesas root.

Ways to Do It Wrong (From Experience)

Ask me how I know!

Forget the Intermediate Cert

The HTTPS client needs to see all of the intermediate certs that make up the chain of trust, if you forget to include it (or them, if there are multiple), then the client has no way to match up the leaf cert with one of the root CA certs in it's trusted certificate store and the chain of trust is broken.

It doesn't help that a LOT of server software obfuscates or completely omits how to configure an intermediate cert in their documentation and UI, which makes it easy to forget. But intermediate certs are a standard and usually required thing, so there's always a way to do it, it just may not be obvious.

Put Certs/Keys in the Wrong Order

When multiple certs and the key are concatenated into a single file, they must generally be presented in a particular order, as detailed above. I don't know why this is, as I feel that any TLS libraries should be smart enough to examine each PEM section individually and work what each one is for. This is one of those things that contributes to the graying of hair for no good reason.

Don't Test After Deployment

Your cert works fine in development but users get a TLS error after deployed to production, eh? It's not entirely your fault. To make it work correctly, you have to get everything set up just right. To break it entirely, you only need to get one thing wrong.

So the first thing I do after deploying a new service or a new certificate is to validate that TLS is working correctly. Generally the OpenSSL command I mentioned under "Verifying Certificate Configuration" is the first thing I do. If that works, there's a 99% chance I did it right. If I'm in a very thorough mood, I will also bring the site up in a few different browsers, and in a couple different OSes if I can manage it.

Suggested Best Practices

A few things that could make your life easier.

Comment Your Certs

When saving a cert to a file, always save the text of the certificate along with the PEM encoding. Think of it like adding comments to obtuse code. This makes the cert both human-readable and machine-readable, and will save you a ton of time when debugging a certificate issue, or just figuring out which cert is which. OpenSSL can do this:

openssl x509 -in cert_file.crt -text > annotated_cert_file.crt

Consider Keys to be Immutable

It is generally considered safest and securest if the TLS key is generated on the host it's meant for, and never ever leaves that host. Copying a key around leaves room for it to get accidentally copied (or left) somewhere it shouldn't be. And then you gotta re-key and re-cert the host if you want any semblance of actual security.

Related: When a cert is expiring soon and you are tasked with renewing it, you may as well re-generate a new key. It's only one extra command and provides a little bit of insurance against your previous key leaking out unbeknownst to you.

Automate What You Can

Let's Encrypt proved that certificate automation was not only possible but even potentially easy. If you're managing purchased certs by hand like some neanderthal, you will find it very worth your time to look into how to automate your cert issuance and deployment, if for no other reason than to avoid a surprise cert expiration at 3 a.m. on a Sunday morning.

Aside: Certificate Files and Formats

You are probably most used to seeing certificate files and keys in PEM format with its BEGIN CERTIFICATE and END CERTIFICATE markers with the base64-encoded data in between. This data is encoded for easily handling but certificate data is actually binary data in an x509 structure. That said, there are other formats out there that you may have to deal with:

- PEM (Privacy-Enhanced Mail): Described above. The most common extension for these is

.crtfor certs, but some software and CAs will use.ceror.pem. Keys usually have the extension.key. - DER (Distinguished Encoding Roles): Simply the binary format for certs, the same data that gets base64-encoded for PEM certs. The extension is usually

.derbut sometimes.crt. - PKCS12: a format used to bundle certs and keys into one file. Primarily used by Java. The file extension is usually

.p12. - PKCS7: Used by Windows and their CA. The extension is usually

.p7b.

There are lots of tools for converting between formats, here is how to do it with OpenSSL:

PEM to DER

openssl x509 -in cert.crt -outform der -out cert.der

DER to PEM

openssl x509 -in cert.der -inform der -outform pem -out cert.crt

PEM to PKCS12

Convert the key and cert into a PKCS12 file. Note that a passphrase is actually required here.

openssl pkcs12 -export -in example.crt -inkey example.key -out example.p12 -name example

Verify that it worked (if you have Java's keytool installed):

keytool -v -list -storetype pkcs12 -keystore example.p12

PKCS12 to Java Keystore (JKS)

keytool -importkeystore -deststorepass changeme \

-destkeypass changeme -destkeystore example.jks \

--srckeystore example.p12 -srcstoretype PKCS12 \

--srcstorepass changeme -alias example

PKCS7 to PEM

openssl pkcs7 -in example.p7b -outform pem -out example.crt -print_certs

Don't Panic 👍

If you're new to managing certificates this might seem like quite a lot of ground to cover, but try not to worry. The good news is that this stuff has been around for a long time and the vast majority of your questions are only a quick search away. Once you understand the fundamentals of the chain of trust and exactly what the browsers are looking for, you're about 95% of the way to being a TLS expert. In my experience, becoming known around your sphere of influence as, "That Guy/Gal Who Knows Things About TLS" is generally all upside. But even if that is not your goal, hopefully this write-up still made the whole thing a bit more approachable.

Rejected Titles

- Certs, HTF Do They Even Work?

- Encryption Intensifies

- If You Liked it Then You Should Have Put a Cert on It

Addendum

Over on the Lobste.rs thread, mcpherrinm provided some excellent additional tips and clarifications on cert formats/extensions.

-

Their only business model, mind you, was to take money in one end, and emit some mathematically-derived bits out the other end. As it were. ↩

-

Except for privacy and Rick Astley memes. ↩

-

As it happens, newer versions of the HTTP protocol make TLS a mandatory part of the protocol. This negates the architectural advantages of separating orthogonal concerns from each other but in theory promotes better security, as long as users of the new protocols get all of their other security practices right. You win some, you lose some. ↩

-

Theoretically speaking, you could be a CA, if you wanted to. Because generating and signing certificates is actually really easy. Getting others to trust you is the hard part. ↩

-

There is, surprisingly, no one industry-standard common term for the final certificate in a chain of trust. Most of the time, people just call it "the certificate," or sometimes "service certificate". I find these to be ambiguous enough to be worth avoiding. A long time ago, I read something that used the phrase "leaf certificate." That's what I'm going with because I like the tree analogy and because it fits in well with the hierarchical DAG arrangement of certificate trust. ↩