There are many things you can do in ham radio and one of the things I like doing is contests. In a contest, you get on the air and try to rack up as many contacts are you can. A "contact" is essentially just getting someone else's attention and exchanging a small amount information with them. A typical contact looks something like this but with ham radio jargon and call signs instead of Midwestern pleasantries:

- Alice: Hello, is anyone out there?

- Bob: Hello Alice, this is Bob.

- Alice: Hi Bob, you are the 103rd person I've talked to today. I'm in Michigan.

- Bob: I received your information. You are the 37th person I've talked to today. I'm in Iowa.

- Alice: Okay, I received your information as well. Have a nice day.

- Bob: You have a good one too.

Each side logs the contact in their computer and then moves on to someone else they haven't talked to yet. At the end of the contest, you submit your logs to whatever organization is running the contest. The organizers process everyone's logs and rank them according to a scoring system. Ham radio contests don't have prizes other than (barely any) bragging rights and maybe a few warm fuzzies. Sometimes you might receive a paper or PDF certificate that you can frame and hang on the wall. But overall, contrary to popular belief, ranking high in a ham radio contest is unlikely to get you international recognition, fancy yachts, or a co-starring role in an upcoming Nicholas Cage movie.

There are various contests held throughout the year, but the biggest one by far is Field Day in June. Part of the point of Field Day is to set up your station in some temporary location (quite possibly an actual field) and run it from something other than the national power grid. (Gas generator, solar, wind, etc.) I also like to participate in other contests when I find the time, so this station setup is designed around that. But Field Day is definitely my favorite.

(Important digression: some hams take offense at calling Field Day a contest. It is ostensibly first and foremost a disaster preparedness exercise and public outreach event. Which is true enough. However, the goal is to make contacts on the radio, and there are rules, and they keep score, and rank stations at the end, soooo...)

One of the initial hurdles I ran into early in my research was that there was not a lot of prior art on building exactly the kind of station I wanted. Most hams that get involved with solar and/or portable stations do one of these two things:

- Charge up a small battery before heading out, and then take the battery, a low-power radio, antenna, etc out to a park somewhere. Sometimes the whole setup fits into a backpack because there may be walking or hiking involved. These operators tend to be using CW (Morse code) which goes very far on very little power. They usually only operate for a few hours rather than a whole weekend.

- Install permanent solar panels and batteries and run all of their radios (and maybe some other stuff) and off that in some fixed location in the basement or some corner of their house.

These are not what I'm after, so I didn't have many examples to follow. In my case, I communicate on the radio with my voice rather than morse code so a low-power station (producing under 10 watts of RF energy) isn't really going to cut it. Especially in a contest situation where the bands might be crowded and everyone is struggling to be heard above everyone else. I want to use my Icom IC-718 which has a more typical power output of 100 watts. This means I need a battery big enough to power that, plus a laptop and a few accessories. The battery will be charged via solar panels to (ideally) keep it topped up during the day.

The station is "portable" in the sense that I want to be able to fit it into the back of a car and have it all fit on a card table or small desk, but I won't be hiking through the woods with it. I will likely be operating out of a camper, shed, or perhaps a reasonably stout tent.

As far as cost, I tried very hard to not just throw money at the problem. That's not my style. I wanted to use what I had on-hand or could buy at reasonable prices. Plus, I'm moderately intelligent (depending on who you ask) and know how to engineer some things.

The audience for this is basically hams (probably newer hams) or others who have an interest in this sort of thing but haven't gotten around to properly studying it. So there will be a fair amount of technical detail. None of it is critical to the overall picture, so feel free to skip anything you like.

Important Note: I may include links to products that I bought but these are NOT referral links and I get nothing if you click on them. Everything here I bought with my own money.

Power Budget

My goal is to have enough power to run both the radio and a laptop while keeping both batteries topped up when the sun is shining. To be totally transparent, I bought most of this gear before I wrote this and didn't do much actual math, I just mostly put together some numbers that "felt" right and took a big old SWAG (scientific wild-ass guess) at it. Right then, let's see if I'm hosed!

Before we go any further, you should be aware there there is math in these here parts. But don't worry, it's all easy multiplication and division. Now, to grossly oversimplify some basic concepts and taunt all the electrical engineers in the room with subpar analogies:

- Volts represents the electrical potential of a battery. Analogous (for our purposes) to water pressure, or holding a book off the ground. If a battery is charged, then voltage is always present on its terminals whether or not it is hooked up to anything. Batteries, solar panels, and the wall plugs in your house provide voltage.

- Amps (or "Amperes" to be precise) represent the amount of current flowing through a circuit. Analogous to water flow, or the energy of the book while it is falling. Current coming out of a battery means the battery is being discharged. Current going into a battery charges it. Current is drawn by a load and currently only flows when there is a closed circuit. No current flows to or from a battery if it is not connected to anything. But if you connect a light or motor, then current flows and they turn on.

- Watts is a measurement of power, or the doing of work, at a particular point in time. If you know the voltage of something, and the current flowing through it, then you just multiply voltage and current, and you get watts:

watts = voltage * current

I want to emphasize that all of the above is true for DC (direct current) circuits. AC (alternating current) is way more complicated. By a lot. However, we're not dealing with any AC here so I'll shut up about it now.

Now, let's see roughly how much power I'll need.

According to the Field Day rules, even though I won't be at home, I'll be classified as a home station on emergency power (Class E) because my radio will output more than 5 watts when transmitting and that's the closest category I can fit into. Further, the rules say the batteries may be charged while in use via solar power, and you can charge the batteries from mains power or a generator in the middle of the contest but you give up points if you do so. One interesting loophole (read: not really a loophole) is that you only have to use emergency power for the radio, not necessarily any accessories like a laptop, TV, or EZ-Bake Oven. So I hope to operate both the laptop and the radio off the battery, but I have the option to switch the laptop over to commercial power without running afoul of the rules. That gives us tremendous leeway in terms of power budget.

Now, I am fully aware that I am not guaranteed a bright and sun-shiny day on Field Day. But being an eternal optimist, my ideal situation is this:

- Start the day with fully-charged laptop and station batteries.

- If the sun is out, run laptop and radio most of the day on solar power alone.

- If it's cloudy enough that the solar panels can't keep the battery fully charged, then I will go as long as I can on both batteries. And maybe switch the laptop over to commercial power if it looks like one or the other is not going to last as long as I want. If I have to quit playing radio a little early, that's okay.

- At night time, operate on both batteries until they run out or until I get tired and go to bed.

I have an Icom IC-718 ham radio and at 13.8 volts, and according to the manual it consumes about 1.5 amps (about 20 watts) when receiving. When transmitting, however, it uses a lot more--up to 20 amps (or 276 watts). But there are two crucial caveats that affect the transmitting power:

- Even during contests, I estimate I spend at least 90% of my time listening for and trying to tune in stations that I haven't worked yet and only about 10% of the time transmitting (or less).

- When using voice (single side-band), the power used by the radio is proportional to the audio being spoken. In other words, the radio is only sending (and thus using) a fraction of the max output power after you average it out over the length of the transmission. We can ball-park it at 50% or 140 watts.

So with the radio spending 90% of its time at 20 watts and 10% of its time at 140 watts, that gives us an average of 32 watts used. Excepting breaks to go potty or rustle up some jerky.

Calculation: (20 x 0.9) + (140 x 0.1) = 32

Explanation:

20 watts x 90% duty cycle = 18 watts

140 watts * 10% duty cycle = 14 watts

--------------------------------------

Total = 32 watts

At its most efficient power settings, my laptop uses around 15 watts doing normal tasks. Adding the radio and laptop together up is 47 watts, but let's round up to 50 for simple math. Now, a 50 watt panel will not give you 50 watts except under strict laboratory conditions overseen by highly-trained monkeys. And actual weather varies tremendously. So I'm going to keep it simple and assume that the average panel generates 80% of its rated power for much of the day on a sunny day, 40% on a partially cloudy day, 20% on a mostly-cloudy day, and basically nothing on a heavily overcast day. So doubling the wattage puts us into reasonably safe territory on sunny days. I will hope for a sunny weekend because that should allow me to run the station for as long as I want, but if it's not, then I'll have to size my battery appropriately to cover operating for most of the day.

Panel Summary: Given a sunny day, 100 watts of solar panel should power my radio, laptop, and charge the battery (if needed) for much of the day. Going to 200 watts will be twice as expensive but won't really improve the situation much except on partially sunny/cloudy days. So I will start with 100 watts and then later decide whether to buy another 100 watts once I've had some time with this setup.

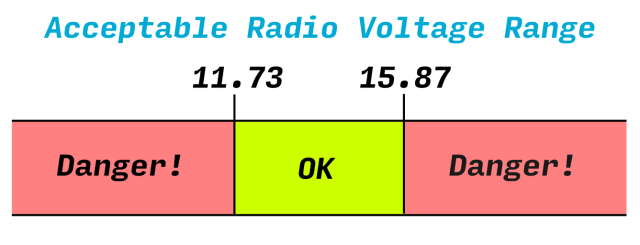

Now the battery. These days, you absolutely want a Lithium-Iron Phosphate (LiFePo4) battery because they are finally ubiquitous, light, have a high charge/discharge cycle count, are pretty safe to use and store (compared to lithium polymer batteries which have a predilection for entering spicy pillow mode), and are quite affordable. These come in a variety of voltages, but we are limited by the voltage range of our radio. Virtually all ham radios are "12 volt" but run on 13.8 volts, plus or minus 15%. This aligns (not coincidentally) with the typical voltage range of a car's electrical system.

Lowest voltage = 13.8 volts - (13.8 volts x 0.15) = 11.73 volts

Highest voltage = 13.8 volts + 13.8 volts x 0.15) = 15.87 volts

So the voltage range of our battery should be between 11.73 and 15.87. Lower is okay, although it might mean losing out on available battery capacity. But going any higher might damage our radio and other gear. Maybe spectacularly, if you are unlucky!

All batteries have a range of voltages that they will supply depending on how charged (or not) they are. They also have a nominal ("middle") voltage and this is mainly for convenience when talking about batteries at dinner parties, so you can just wink and say, "Yeah, my car has a 12 volt battery," instead of, "You won't believe it, my car battery fluctuated between 14.3 and 14.7 volts on the way here!" That kind of talk will not get you invited to any more dinner parties. So play it cool and just casually toss around the nominal voltage unless you are actually measuring the battery for some specific reason.

(If you care, the nominal voltage of a battery is determined by the number of cells wired up in series inside the battery. In the case of a LiFePo4 battery, that number is four. 3.2 volts * 4 cells = 12.8 volts)

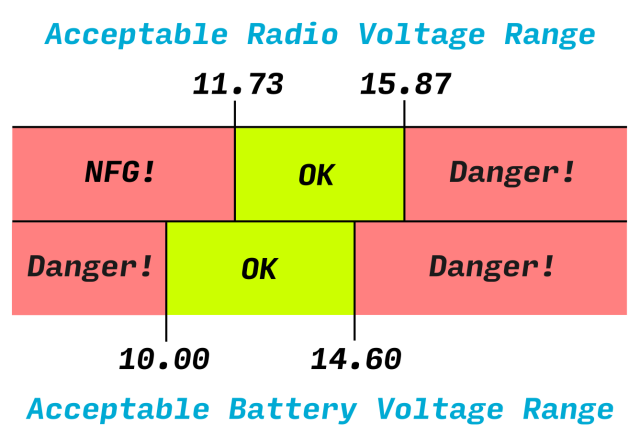

A very typical nominal voltage for a LiFePo4 battery is 12.8 volts. The voltage range for these is between 10 volts and 14.6 volts.

Now, if you don't have much experience with LiFePo4 batteries, you might think these ranges don't match up well at all. It looks like there's a huge dead zone of lost capacity between 10 and 11.73 volts. It's actually nowhere near as bad as it looks because LiFePo4 batteries have a very flat discharge curve:

See those hockey sticks at the extreme ends of the graph? Those represent pretty large voltage swings but very little capacity. Put another way, once the battery is drawn down to 11.73 volts (the lower limit of the radio), almost all of the capacity is already used up anyway. Meaning we really only lose out on a couple percent of charge, at worst. The important bit is that the working battery voltage and working radio voltage have more than enough overlap to be successful for what we want to do.

Next, we need to know the capacity to buy. Battery manufacturers have standardized on amp-hours (Ah) as their unit of capacity. I don't want to go too far into the rhubarb on amp-hours because there is a lot of detail, but suffice to say unless you are pushing a battery hard in terms of charging/discharging current, or you're an engineer whose job it is to spec out battery systems, it's far easier to work backwards by figuring out the watt-hours (Wh) you need first and then dividing by the nominal voltage (of 12.8) to get the amp-hours.

Our speculative load is 50 watts. But that's a point-in-time measurement, not a capacity. To figure out how many watt-hours we need, we take 50 watts and multiply it by how long we want the battery to last at that load. I could probably live with 6 or 8 hours, but let's aim higher and say 12 hours just to see where we are:

50 watts x 12 hours = 600 watt-hours

Now this is a highly conservative value because remember I can disconnect the laptop from the station battery if I want to. But let's stick with the conservative value and figure out the amp-hours:

600 watt-hours / 12.8 volts = 46.875 amp-hours

As it turns out, we're in luck! 50 amp-hours is a very common LiFePo4 12.8 volt battery size. And they are not even physically that big or heavy, just a little smaller than a typical car battery and much, much lighter. Now, don't rush out and buy one just yet, there will be another post describing my odyssey trying to find a decent(ish) battery.

Finally, we also have to pay some attention to the maximum charge and discharge currents of the battery. Often these are the same. They will be given in the battery's manual or spec sheet. You want to make sure the maximum current draw of your station stays well below the maximum current the battery can provide. (If you're right at the limit, or close to it, then you will be pushing the battery pretty hard and can expect a reduced lifespan.) In my case above, we know our worst-case between the radio and laptop is 25 amps, so we need a battery with a higher current rating than that.

Battery Summary: To have 12+ hours of operation, I need roughly 600 watt-hours of capacity, or 50 amp-hours on a 12.8 volt battery. And the maximum charge/discharge current of the battery should be at least 25 amps, but 35 or more would be ideal.

The next post in this series will be about choosing cromulent solar panels for this setup. I'll update this post to put a link to it when it's released but if you can subscribe to my RSS feed if this kind of thing is your jam.

In Part 2, we get into selecting the solar panels for the station.