Topics: Linux, Networking

Internet Mail, or email, or whatever kids these days call it, was one of those things that terrified me very early on when I was a strapping young System Administrator. Everything else that I was doing at the time seemed comparitively easy: Linux/BSD installs, system setup, automation, and such. Learning how various Unix shells and relational databases worked was a joy. But mail server administration... now that scared the hell out of me.

E-mail was and still is a complicated, fragile system. You can do everything right and still end up arse-deep in alligators due to someone else's mistake or bad hair day. There's just so much that can go wrong. To run a successful mail server means that you have to--at a bare minimum--concern yourself with such trivialities as:

- Getting all the DNS records exactly just so.

- Make sure you start with a "clean" IP address... and keep it that way.

- Set up user accounts and authentication.

- Know how to configure the SMTP server.

- Know how to configure the POP/IMAP server.

- Oh yes, and most importantly: don't let the mail server become a spammer's playground.

One of my first jobs was at a managed web hosting provider. Back then, if you wanted to become an expert on Apache, PHP, and email, then working the phones at a company like this was the quickest path "grizzled veteran" status. It's safe to say I learned me some email at that job.

I'm pretty comfortable with mail administration and troubleshooting nowadays. Heck, I even host my own personal mail server. Not out of necessity or anything, mostly just to annoy people on Reddit and HN who say it's impossible. My own setup is pretty stable and very rarely needs any attention. But either at work or at home, I sometimes find myself needing to troubleshoot occasional mail-related issues.

When The Mail Doth Not Flow, one of the most basic things you find yourself doing is sending test messages. Sometimes from systems that don't even have a proper mail server, client, or relay. For better or worse, it turns out that the "simple" in SMTP is not as much of a lie as "lightweight" in LDAP, and you don't often need a lot of ceremony just to fire off a simple message or two for testing or notifications from a barebones system. This article describes a few methods for doing so.

Important: I'm going to use example.com as the domain here for illustrative purposes. This is not, in fact, a real mail server and it will never accept your messages or advances, even if you come armed with flowers and chocolate.

If you want to try some of these out but don't have your own mail server to fool around on, probably the best option is to fire up a Docker container or VM and install Postfix inside it. You can try to send mail to major mail providers using these methods but strive to contain your inevitable outrage if it doesn't work, especially if you are sending from a residential IP address.

SMTP Basics

It's important to know that when you (or perhaps even your mail client) send a message via SMTP, you're not just blasting a request at a server and hoping for a response, as with HTTP. Instead, SMTP more closely resembles a conversation. You say something, the server replies. You say another thing, the server replies again, and so on, until everything that needs to be said has been said and the discussion ends amicably. If you say something out of order, or that the mail server doesn't understand, it will act confused or just rudely hang up on you.

It's also worth pointing out early on that the SMTP standards require CR+LF line endings. (That's a carriage return character 0x0d, followed by a linefeed character 0x0a.) Most mail servers will happily accept stand-alone LF or (heaven forbid) CR line endings, but you shouldn't always count on that. When troubleshooting, you generally want to do things the way they are supposed to be done so as not to be lead down the garden path by your own incompetence, ask me how I know.

Finally, SMTP servers generally listen on TCP port 25, among others. (Other ports might mandate TLS, or refuse to continue without STARTTLS, or require authentication.)

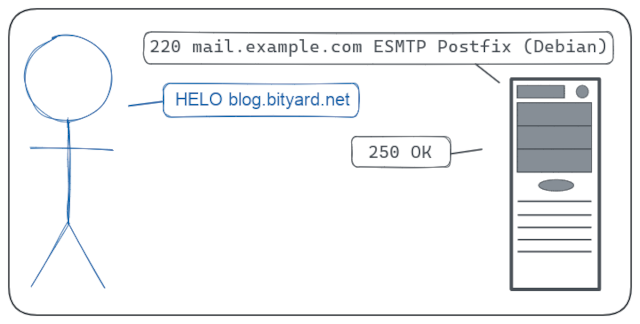

1. Greeting

When you connect to an SMTP server, it will tell you its name and then wait for you to greet it with yours. The first thing you say to a mail server is almost literally, "Hello, I am (insert name here)." You greet the server and tell it the hostname of the machine you're sending mail from.1 If you didn't offend it somehow, the mail server responds simply with 250 OK. In the following example, I have connected to the mail server at mail.example.com and told it that my own hostname is blog.bityard.net:

Different mail servers reply with different text, the important bit is that the response starts with 250. That's SMTPese for, "I don't hate you yet, let's keep talking."

You can also use EHLO instead of HELO. All this does is tell the server that you're a client that can handle SMTP features invented within the last 30 years or so. For the purposes of courageous troubleshooting or intrepid messing around, it doesn't really matter much which one you use but I'll be using EHLO from now on because it sounds more British.

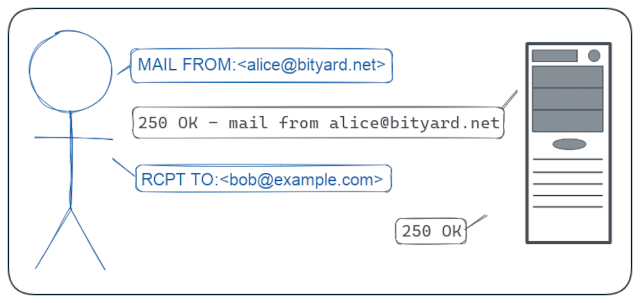

2. Envelope

Next we say who the message is from and who the message is to.

3. Message

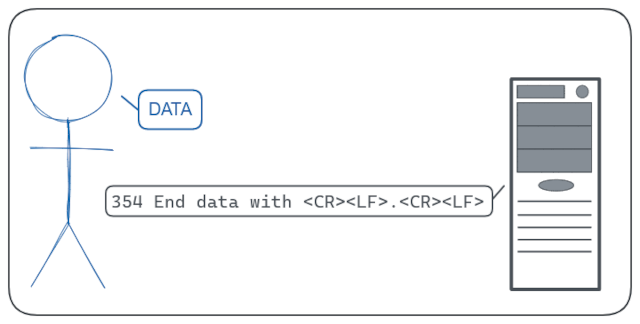

If you've made it this far, there's a fair chance the server will accept the message and it might actually even deliver it. So we tell it that we're about to send the message:

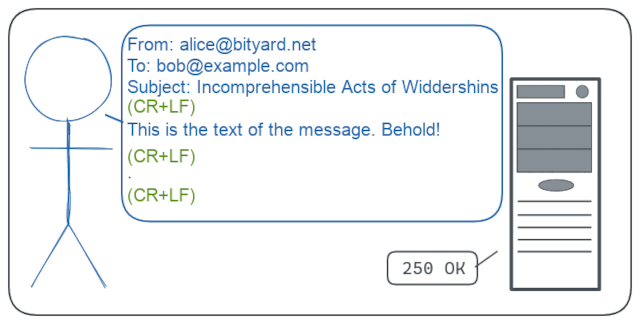

This means the server is ready to accept the message. Each mail message consists of two parts, the headers and the body. These must be separated by a blank line. (If you're reading this article, I'll presume you know what email headers are.) Note that the mail server is helpfully telling you how to signal the end of the message: A blank line, a dot, and another blank line. Here's an example of what to send:

Note that different mail servers tend to respond to confusion in the headers in different ways. The To and From headers don't always have to match what you put in the envelope (this is to allow for things like mailing lists and forwarding to work), and technically a Subject header is optional. But a lot of things will go easier for you in life if you don't try to optimize for the smallest possible character count.

If the server was not terribly displeased by your inane ramblings, it accepts the message. Note that the mail server can still do whatever it wants with the message after acceptance. Up to and including:

- deliver it into a user's mailbox

- forward it to another mail server

- drop it on the floor (unceremoniously delete it)

- broadcast it into outer space via radio signal to show alien civilizations that there is no intelligent life here

If at any point you feel like you have made a sufficient fool of yourself, you can always bail out with the QUIT command or just close the TCP connection.

The Telnet Way

Telnet is ostensibly its own protocol, not just some low-level TCP client. But in practice it often works as one anyway, and we can use it to manually simulate a number of other protocols such as SMTP. This is the closest some of us will ever get to being one of those super-cool computer hackers in action movies that save the day by cracking a military-grade encryption algorithm with seconds left to spare.

To send a message, run the telnet command with the server hostname and TCP port number as arguments:

$ telnet mail.example.com 25

Trying 127.0.0.1...

Connected to mail.example.com

Escape character is '^]'.

220 mail.example.com ESMTP Postfix (Ubuntu)

Although as we noted above that regular newlines will probably work, the proper and correct thing to do is to switch telnet's line endings to CR+LF. To do that, type ^] followed by Enter and then:

^]

telnet> toggle crlf

Will send carriage returns as telnet <CR><LF>.

From this point on, continue sending your message:

HELO blog.bityard.net

250 OK

MAIL FROM:<[email protected]>

250 OK - mail from [email protected]

RCPT TO:<[email protected]>

250 OK

data

354 End data with <CR><LF>.<CR><LF>

From: [email protected]

To: [email protected]

Subject: Why are fish so easy to weigh?

Because they have their own scales.

.

250 OK

quit

221 BYE

The Netcat Way

If your Unix machine is far too modern and hip to have an old fossil like telnet lying around, then perhaps it has netcat? If so, the process is largely similar, except you start the program with the -C flag to tell netcat to use CR+LF line endings:

$ nc -C mail.example.com 25

From here, your port is open and you can just bash out the conversation on your keyboard.

Since netcat is, after all, designed to be stuffed into pipelines, you could conceivably put your half of the conversation into a file and just blast it at the server, right? Well, you could try, and you will sometimes even get away with it. Remember what I said above: SMTP is a conversation. If you start barking multiple commands at the server without waiting for a response in between, it will complain because that isn't a conversation.[^pipelining]

There is a cheap hacky work-around to this, though: you can tell netcat to wait a certain amount of time between sending lines, in order to give the server time to respond to commands. This will often work, but you'll want to pay attention and adjust the interval when working with particularly lethargic mail servers. (And I certainly do NOT recommend doing this for any kind of permanent solution. It is very brittle.)

Here is what a file called test.smtp might look like (be sure to use CR+LF line endings in the file!):

HELO blog.bityard.net

MAIL FROM:<[email protected]>

RCPT TO:<[email protected]>

DATA

From: [email protected]

To: [email protected]

Subject: Originally, I didn't like having a beard.

But then it grew on me.

.

QUIT

And this is how you would send it.

nc -C -i 1 mail.example.com 25 < test.smtp

The Python Way

One of the better ways to send a message from a host that has Python installed is with a short script. This is made possible by virtue of Python's built-in smptlib module. The nice thing about this is that it's highly flexible and doesn't require any other local mail server or tools.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import smtplib

from email.message import EmailMessage

msg = EmailMessage()

msg['From'] = '[email protected]'

msg['To'] = '[email protected]'

msg['Subject'] = 'Every time you swallow some food coloring...'

msg.set_content('...you dye a little inside.')

smtp = smtplib.SMTP('mail.example.com', 25)

smtp.set_debuglevel(2)

smtp.send_message(msg)

smtp.quit()

The Sendmail Way

Unix greybeards will remember Sendmail, possibly as a motivation for taking up a burning interest in the hobby of drinking to excess. As a mail server, it has mostly been supplanted by more modern and sensible options. But several parts of its legacy live on and one of those is the sendmail client for sending mail from the command-line.

The sendmail command allows one to to write (or of course generate) a message in a standard format and then send it on its way to a mail server. If the host you're logged into has a mail server running on it (such as Sendmail, Postfix, Exim, etc), then the sendmail command is likely available. There are also stand-alone mail transfer agents that only accept messages and forward them along to some "real" mail server. (The one that I usually reach for is msmtp.)

If a sendmail command exists on the host, you can use it to send messages which were written as text files. Let's assemble the following message as my_message.eml in the text editor of your choice:

From: [email protected]

To: [email protected]

Subject: I recently developed an irrational fear of elevators

Since then, I have been taking steps to avoid them.

Notice that the top of the message has headers followed by a blank line, followed by the message. Theoretically, only the To header is required, but it depends on which sendmail variant you have installed. It's a good idea to include all three in any case, it will possibly make your life less interesting-but-in-a-bad-way.

You can send it with:

sendmail -vt < my_message.eml

The -v flag tells the command to report what it's doing (useful when troubleshooting) and the -t flag tells it to read the recipient(s) from the headers in the message itself. Your sendmail implementation may have other options to investigate. Feel free to peruse them with man sendmail.

The Swaks Way

On systems with Perl (or a package manager that can install one), Swaks may be an option.

Swaks describes itself as a "Swiss Army Knife for SMTP". The nice thing about Swaks is that it lets you test and verify aspects of your SMTP configuration that would otherwise take a lot of setup or custom code. You can use it to test encryption (TLS, STARTTLS), authentication, SMTP protocol variants, sockets, proxies, and a whole bunch more.

See the docs for full details, but a simple test message can be sent with:

swaks --to [email protected] --server mail.example.com

The Bash Way

I present this way last because of the ways presented to far, this one is the most ill-advised. It's here mainly for completeness and and probably should not be used for anything serious except by those afflicted with chronic self-loathing. In any case, you do you.

Bash has this one weird trick where you can open a TCP (or UDP) port to another host and read and write to it with a file descriptor. This means you can (in theory) write a Bash script to communicate with any Internet service. Now, Bash is good at a great many things, but writing a robust SMTP client would be quite a challenge. Nevertheless, if we sacrifice our sanity a little and don't mind some repetition, we can get away with the bare minimum needed to send a message.

The following script was lightly modified for clarity but was based on this answer from Stack Overflow.

#!/usr/bin/env bash

readonly smtp_host=mail.example.com

readonly smtp_port=25

readonly msg_from=[email protected]

readonly msg_to=[email protected]

readonly msg_subject='Why did the scarecrow win an award?'

readonly msg_body='Because he was outstanding in his field.'

# send a line ending in a carriage return followed by an implicit line feed

# (`echo` prints a line feed at the end of each line automatically)

send() {

echo -e "$@\r" >&3

}

# check the status code returned by the server

# if it's not what we expect, bail out

check_status () {

expect=250

if [ $# -eq 3 ] ; then

expect="$3"

fi

if [ $1 -ne $expect ] ; then

echo "Error: $2" >&2

exit

fi

}

# open a TCP connection to the mail server

exec 3<>/dev/tcp/$smtp_host/$smtp_port

read -u 3 status text

check_status "$status" "$text" 220

# greet the server

send "HELO $(hostname -f)"

read -u 3 status text

check_status "$status" "$text"

# send the envelope

send "MAIL FROM: $msg_from"

read -u 3 status text

check_status "$status" "$text"

send "RCPT TO: $msg_to"

read -u 3 status text

check_status "$status" "$text"

# send the message

send "DATA"

read -u 3 status text

check_status "$status" "$text" 354

send "From: $msg_from"

send "To: $msg_to"

send "Subject: $msg_subject"

send

send "$msg_body"

send

send "."

read -u 3 status text

check_status "$status" "$text"

In Conclusion

I am terrible at writing conclusions. This is the end of the article, I hope you enjoyed it.

-

Real Mail Servers out there in Cyberspace may try to verify that you are who you say you are with a DNS lookup or two and might close the connection if they think you are lying. But on an internal mail relay or somesuch, you can often get away with some degree of subterfuge. ↩

-

The more experienced readers among us will note that all modern mail servers these days support pipelining, but pipelining only helps you blast some commands at a server in rapid-fire fashion, not all. ↩